Last week, ASTC attended the SIA CESA conference, organized by La Société des Ingénieurs de l’Automobile (the French society of automotive engineers). The conference theme this year was SDV, the Software-Defined Vehicle and new electronics architectures. It covered two days of talks plus an exhibition. We were there to learn and talk to partners and other players in the automotive ecosystem.

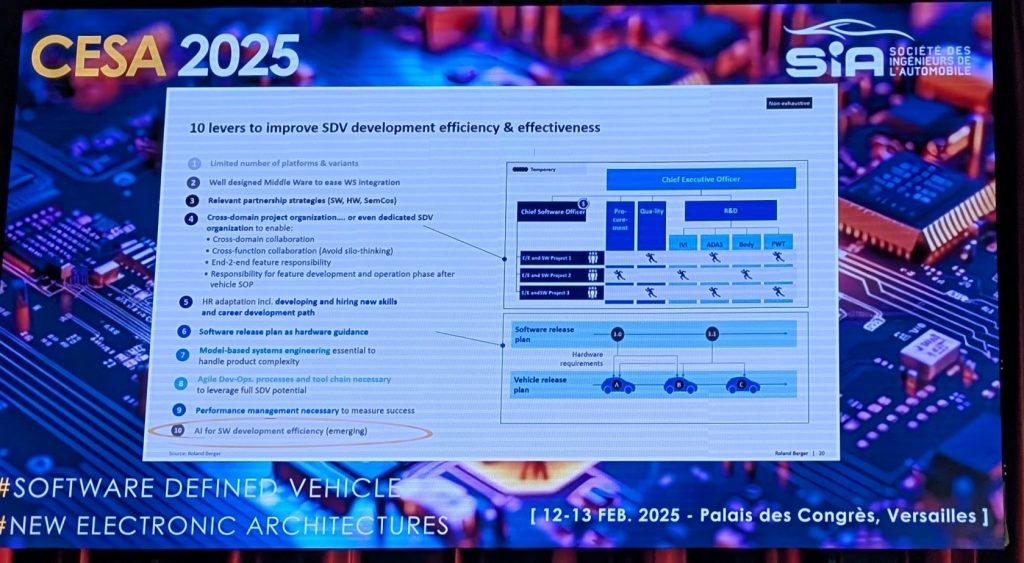

The main theme was well and truly SDV. I stole the quote in the title from the keynote by Eric Dequi from Stellantis, who pointed out just how much has to change to truly achieve a software-defined vehicle architecture. It is not just the software, but also the underlying hardware architecture, how you organize development, the design of your vehicle platforms for product lines, all the way up to C-suite planning. When SDV hits your designs and products, you have to change your mindset. Continuing as we have in the past will not work.

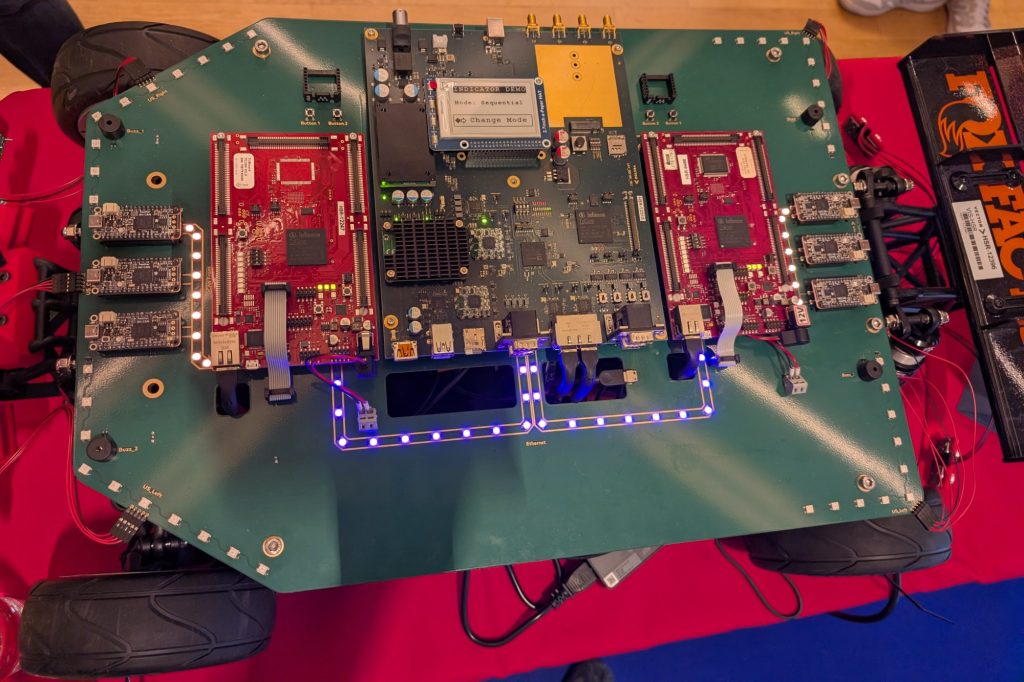

The Vector booth contained a very pedagogical setup demonstrating the essence of a modern Zonal vehicle architecture: an ARM-based main processing board flanked by two Tricore-based zone controllers, connected to a multitude of sensors and actuators. Most diagrams of vehicle architectures shown in the talks at the conference followed this general pattern, obviously with lots of variation and different numbers of high-performance compute (HPC) nodes and zones. But the three-tiered systems are everywhere.

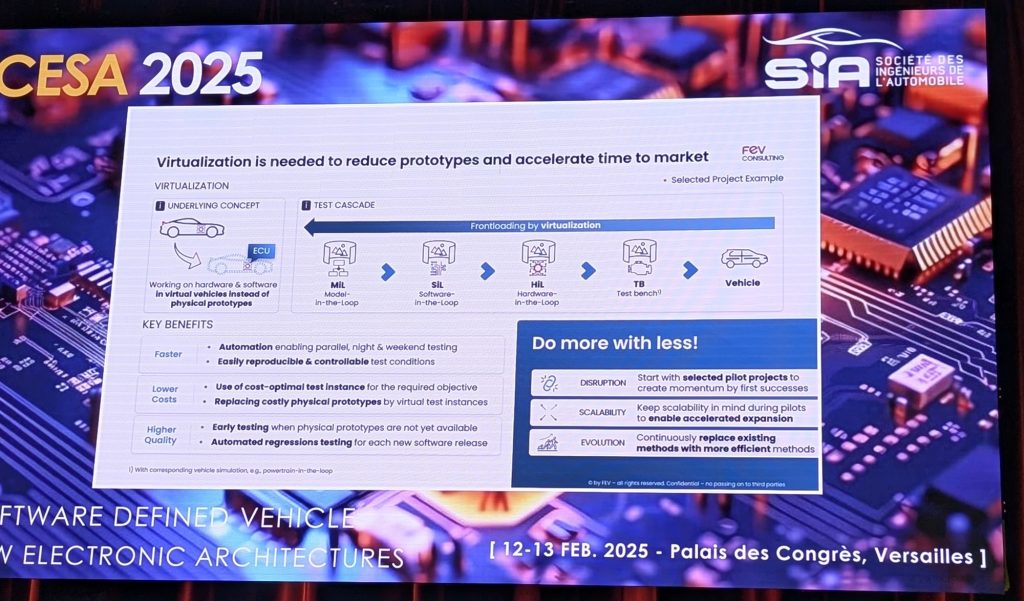

SDV requires much more agile and efficient software development and testing methodologies, and a key component of that is virtualization. It is critical to be able to run software for testing without requiring physical development boards and physical test systems. Which is exactly what we do at ASTC – we provide virtual ECUs that run the same software as real ECUs, and can be combined into networks that mimic the real vehicles.

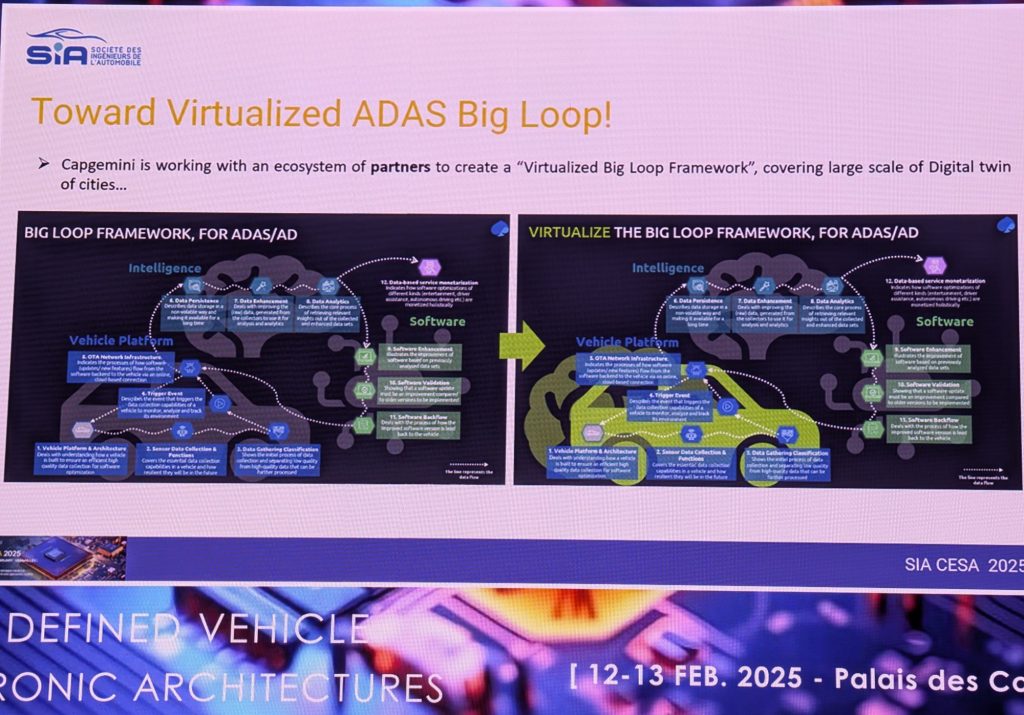

Beyond the software and electronics, the vehicle and the world around the vehicle must also be part of the virtualized system. To achieve this, it is necessary to integrate many different simulators into a coherent whole. It might “just” be some electric motors or batteries, or it might go all the way to simulating entire cities to allow virtual test drives where simulated sensors view the simulated world. Including the weather and time of day – a rainy night is quite different from a dry sunlit day.

The only way to make software testing work at this scale is to automate it. This goes under many names. Some people at the conference talked about DevOps, others called it continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD), and yet others called it software factory. The idea in all cases is that software should just flow through a sequence of build and test steps without the developer or testers having to inject manual actions. Key to that is once again simulation and virtualization – automating hardware is hard, automating software is (comparatively) easy.

It cannot be 2025 without talking about Artificial intelligence, AI, and it was brought up in several talks. Typically, as a technique that can increase productivity for software developers – with numbers from 20% to 50% being thrown around. Applications suggested included helping software engineers generate code and tests, as well as some more larger flows where generative AI can transform information from one form to another. There is also the potential to improve the user experience of a vehicle, in particular for as a way to diagnose issues with a vehicle and smoothen the service experience.

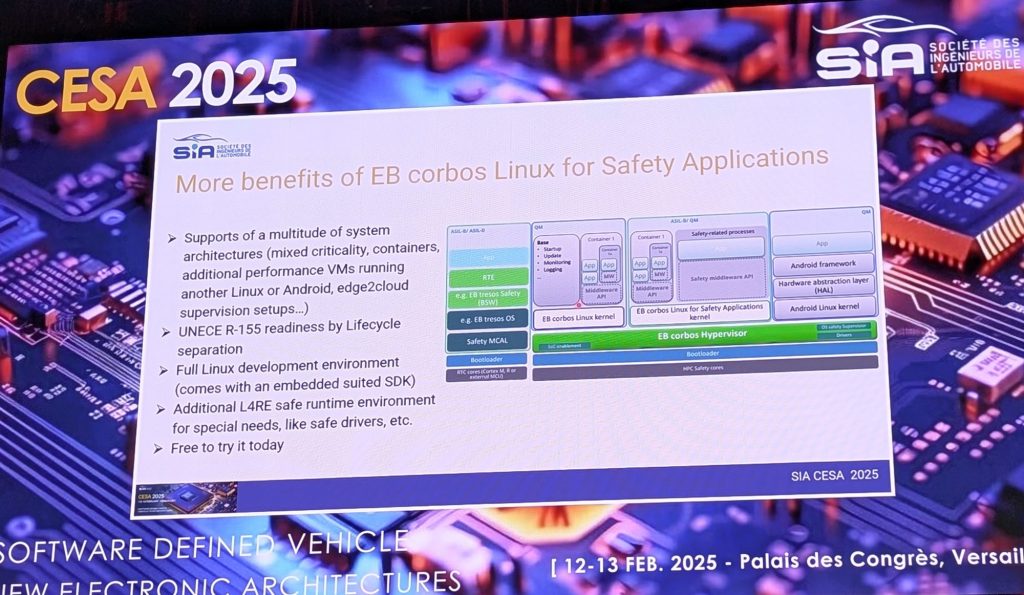

Centralizing vehicle compute into one or more HPC nodes depend on another type of virtualization – runtime virtualization implemented using a Hypervisor. The high-level concept is simple enough: run a Hypervisor on the hardware and put software of different criticalities and different nature into different guest virtual machines. The Hypervisor will keep the isolated system function safe. The details vary a lot depending on which company you talk to, though. No matter what, you can run the whole software stack on a fast simulator (the type of virtualization we mentioned before).

The conference was held in the wonderfully weird Palais de Congrès in Versailles. The venue inside the building contains a round(ish) exhibition hall and an amphitheater on top of the hall. The logo reflects the rounded shape this in a way that is just perfect. The main amphitheater was wonderfully plush (see top photo), and it seems the venue doubles as a concert hall.

With staircases that follow the rounded shape of the amphitheater, it is sometimes hard to get a good sense of direction. Indeed, it feels a bit like a map from a classic FPS like Unreal Tournament where you run out a door into a staircase and suddenly realize you found another way back to where you started… while having no real idea which direction you are facing. It does not help that additional small conference rooms are stacked vertically on to of the main amphitheater hall – but only some staircases lead to the rooms above the main room. According to a plaque in the building, it was built in 1967. It is a bit reminiscent of Terminal 1 at Charles-de-Gaulle that was built in the same era, good examples of French science-fiction-inspired modern architecture of the late 1960s.